alb3673853

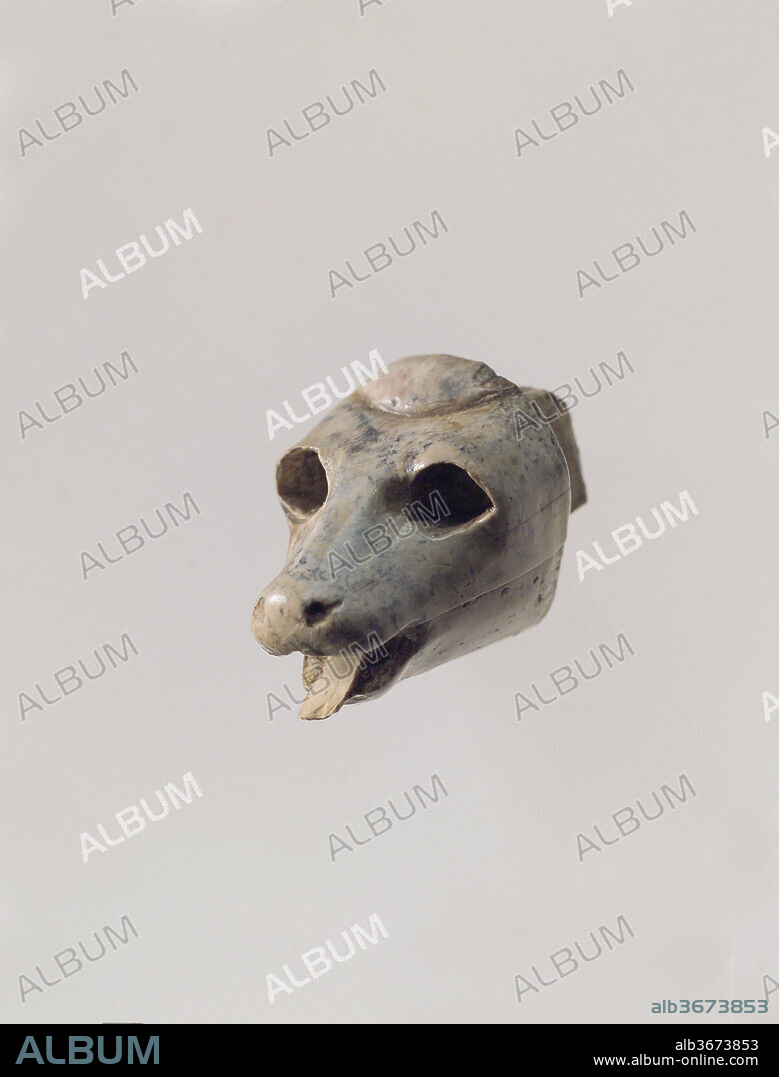

Animal head carved in the round

|

Zu einem anderen Lightbox hinzufügen |

|

Zu einem anderen Lightbox hinzufügen |

Haben Sie bereits ein Konto? Anmelden

Sie haben kein Konto? Registrieren

Dieses Bild kaufen

Titel:

Animal head carved in the round

Untertitel:

Siehe automatische Übersetzung

Animal head carved in the round. Culture: Assyrian. Dimensions: 0.55 x 0.59 x 0.91 in. (1.4 x 1.5 x 2.31 cm). Date: ca. 8th-7th century B.C..

This carved ivory head was found in a storage room in Fort Shalmaneser, a royal building at Nimrud that was used to store booty and tribute collected by the Assyrians while on military campaign. It depicts an animal with a long, narrow snout, mouth open and tongue extended, and large eyes that would have been inlaid with materials in contrasting colors. A tenon at the back of the head would likely have been used to attach the head to the animal's body, perhaps carved out of another piece of ivory or a different material. Carved ivory pieces such as this were widely used in the production of elite furniture during the early first millennium B.C. They were often inlaid into a wooden frame using joinery techniques and glue, and could be overlaid with gold foil or inlaid to create a dazzling effect of gleaming surfaces and bright colors. The piece may have represented a dog, as the nose resembles that of a canine rather than the broader snout of a sheep or goat, and the deep-set eyes face forward rather than to the sides, indicating the animal was a hunter. Dogs rarely appear in the decoration of the carved ivory furniture and small luxury objects collected by the Assyrian kings. However, dogs are fairly common in the art of ancient Mesopotamia in other contexts, and are shown as a wide range of types, including thick-necked guard dogs wearing collars (see 1989.233 in the Metropolitan's collection), small dogs with curled tails associated with the healing goddess Gula, and hunting dogs resembling the modern saluki. This ivory head most closely resembles the latter.

Built by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, the palaces and storerooms of Nimrud housed thousands of pieces of carved ivory. Most of the ivories served as furniture inlays or small precious objects such as boxes. While some of them were carved in the same style as the large Assyrian reliefs lining the walls of the Northwest Palace, the majority of the ivories display images and styles related to the arts of North Syria and the Phoenician city-states. Phoenician style ivories are distinguished by their use of imagery related to Egyptian art, such as sphinxes and figures wearing pharaonic crowns, and the use of elaborate carving techniques such as openwork and colored glass inlay. North Syrian style ivories tend to depict stockier figures in more dynamic compositions, carved as solid plaques with fewer added decorative elements. However, some pieces do not fit easily into any of these three styles. Most of the ivories were probably collected by the Assyrian kings as tribute from vassal states, and as booty from conquered enemies, while some may have been manufactured in workshops at Nimrud. The ivory tusks that provided the raw material for these objects were almost certainly from African elephants, imported from lands south of Egypt, although elephants did inhabit several river valleys in Syria until they were hunted to extinction by the end of the eighth century B.C.

Technik/Material:

MARFIL

Zeitraum:

NEOASIRIO

Museum:

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Bildnachweis:

Album / Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Freigaben (Releases):

Model: Nein - Eigentum: Nein

Rechtefragen?

Rechtefragen?

Bildgröße:

2870 x 3774 px | 31.0 MB

Druckgröße:

24.3 x 32.0 cm | 9.6 x 12.6 in (300 dpi)

Schlüsselwörter:

Pinterest

Pinterest Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Link kopieren

Link kopieren Email

Email