alb3669576

Head of a male or female figure

|

Add to another lightbox |

|

Add to another lightbox |

Title:

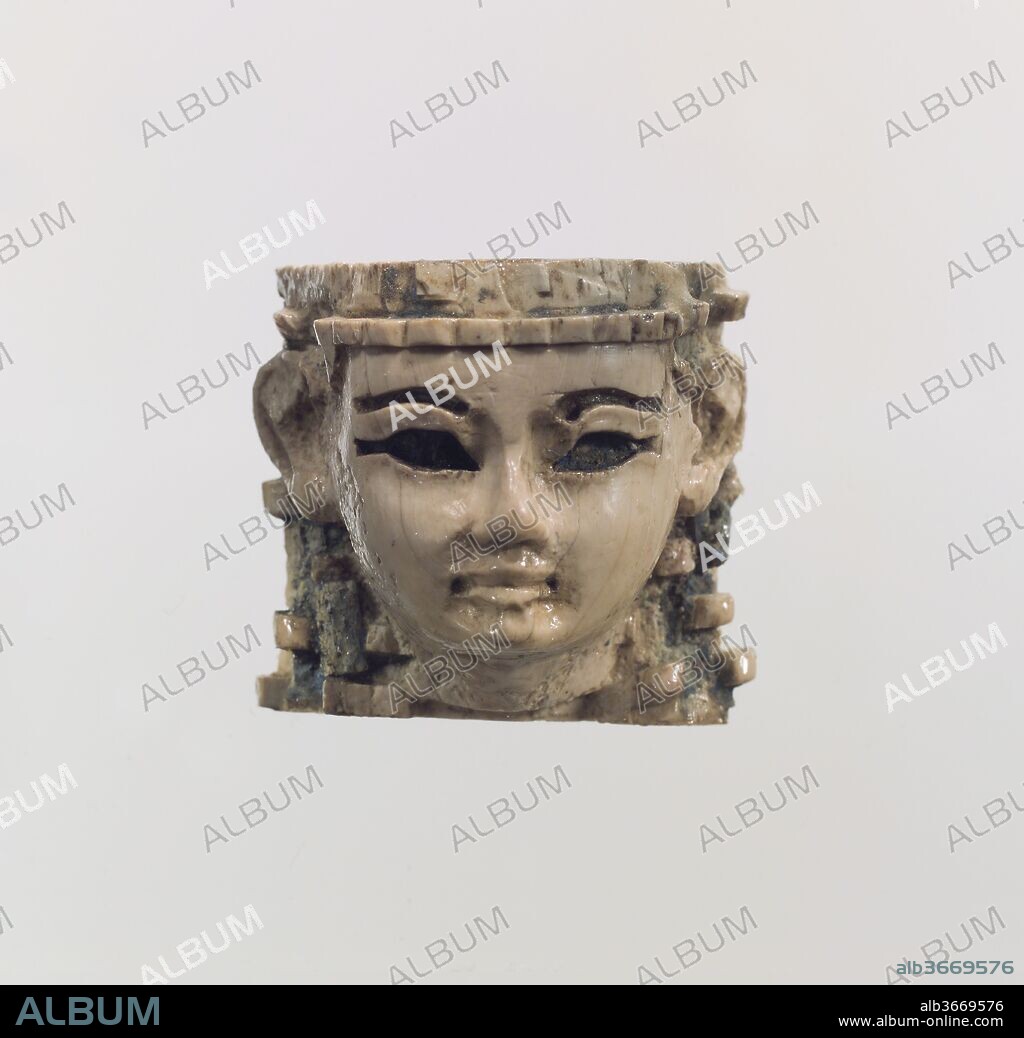

Head of a male or female figure

Caption:

Head of a male or female figure. Culture: Assyrian. Dimensions: 1.02 x 1.14 in. (2.59 x 2.9 cm). Date: ca. 9th-8th century B.C..

This small ivory head is beardless and its gender cannot be securely determined. It was found in a room at Fort Shalmaneser, a royal building at Nimrud that was probably used to store tribute and booty collected by the Assyrians while on military campaign. Originally, the head may have been part of a composite statuette, made of various materials and painted or overlaid with gold foil. The top and reverse have been roughened, probably to help glue join the surface of the ivory to another piece made out of wood or ivory that comprised the upper part and back of the head. The soft modeling and use of inlays, now missing, in the deeply cut eyes and eyebrows are characteristic of Phoenician ivories. The wig is tied by knots at intervals and preserves some of its original inlay of Egyptian blue, a vibrant artificial pigment made of silica, lime, copper, and alkali. Another Phoenician-style ivory head found at Nimrud is also in the Metropolitan Museum's collection (MMA 62.269.2).

Built by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, the palaces and storerooms of Nimrud housed thousands of pieces of carved ivory. Most of the ivories served as furniture inlays or small precious objects such as boxes. While some of them were carved in the same style as the large Assyrian reliefs lining the walls of the Northwest Palace, the majority of the ivories display images and styles related to the arts of North Syria and the Phoenician city-states. Phoenician style ivories are distinguished by their use of imagery related to Egyptian art, such as sphinxes and figures wearing pharaonic crowns, and the use of elaborate carving techniques such as openwork and colored glass inlay. North Syrian style ivories tend to depict stockier figures in more dynamic compositions, carved as solid plaques with fewer added decorative elements. However, some pieces do not fit easily into any of these three styles. Most of the ivories were probably collected by the Assyrian kings as tribute from vassal states, and as booty from conquered enemies, while some may have been manufactured in workshops at Nimrud. The ivory tusks that provided the raw material for these objects were almost certainly from African elephants, imported from lands south of Egypt, although elephants did inhabit several river valleys in Syria until they were hunted to extinction by the end of the eighth century B.C.

Technique/material:

IVORY

Period:

NEO-ASSYRIAN

Museum:

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Credit:

Album / Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Releases:

Model: No - Property: No

Rights questions?

Rights questions?

Image size:

3749 x 3605 px | 38.7 MB

Print size:

31.7 x 30.5 cm | 12.5 x 12.0 in (300 dpi)

Keywords:

Pinterest

Pinterest Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Copy link

Copy link Email

Email