alb3603041

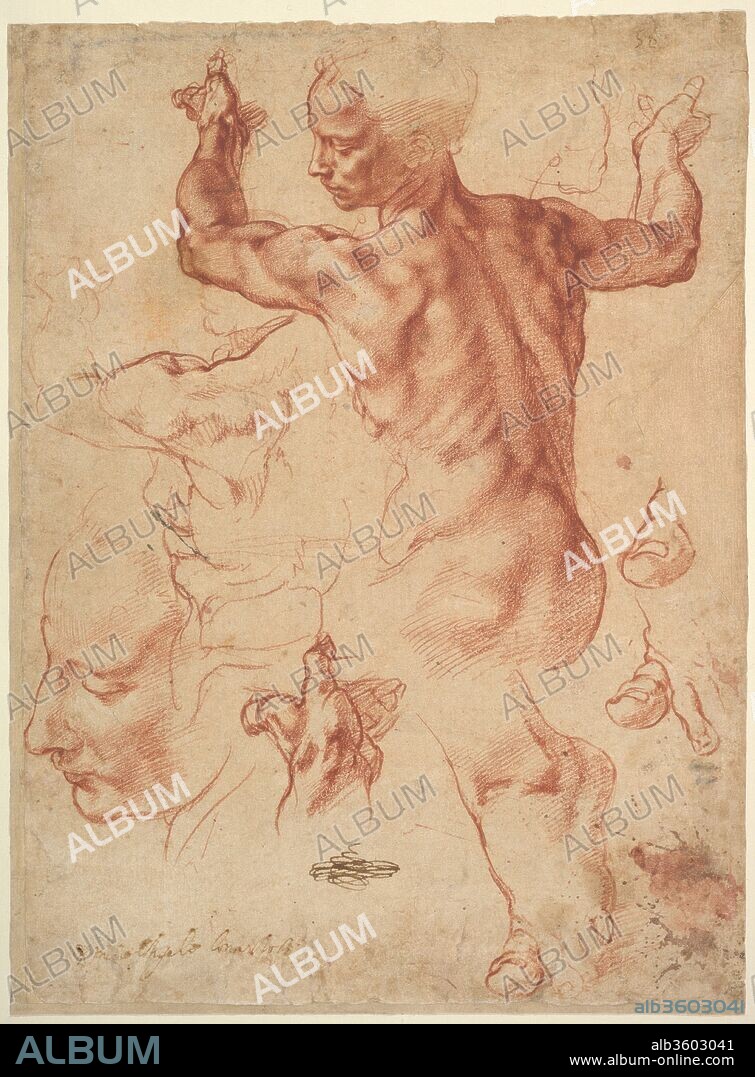

MIGUEL ANGEL. Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto); Studies for the Libyan Sibyl and a small Sketch for a Seated Figure (verso)

|

Añadir a otro lightbox |

|

Añadir a otro lightbox |

¿Ya tienes cuenta? Iniciar sesión

¿No tienes cuenta? Regístrate

Compra esta imagen

Título:

Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto); Studies for the Libyan Sibyl and a small Sketch for a Seated Figure (verso)

Descripción:

Traducción automática: Estudios para la sibila libia (anverso); Estudios para la sibila libia y un pequeño boceto para una figura sentada (verso). Artista: Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italiano, Caprese, Roma, 1475-1564). Dimensiones: Hoja: 11 3/8 x 8 7/16 pulg. (28,9 x 21,4 cm). Fecha: ca. 1510-11. Esta hoja de doble cara de estudios de vida observados de cerca es el dibujo más magnífico de Miguel Ángel en América del Norte, comprado por el Museo Metropolitano de Arte el 8 de agosto de 1924 (su adquisición fue votada por el comité de adquisiciones del museo el 9 de junio de 1924). , en gran parte gracias a las negociaciones del eminente pintor John Singer Sargent con la viuda de Aureliano de Beruete, su anterior propietario (expediente núm. D7950, Departamento de Archivo de Dibujos y Grabados, Museo Metropolitano de Arte). Los estudios mucho más pequeños que el tamaño natural en el famoso anverso de la hoja Metropolitan fueron claramente realizados por un joven asistente posando en el estudio del artista, como preparación para el diseño de la Sibila Libia, la monumental figura femenina entronizada pintada al fresco en el extremo noreste del Techo Sixtino. La sibila libia fue la última de los videntes en ser pintada con un fresco en la parte norte de la bóveda, ejecutada en una escala que es aproximadamente tres veces el tamaño natural (el área total de esta parte en el fresco mide 4,54 metros por 3,80 metros); está vestida excepto por sus poderosos hombros y brazos, y lleva un elaborado peinado trenzado. Su compleja postura en el fresco, que evidentemente requiere estudio en numerosos dibujos, juega con el movimiento detenido de ella bajando del trono, mientras sostiene un enorme libro abierto de profecía que está a punto de cerrar. Esbozado con suave tiza negra, el reverso de la hoja Metropolitan de doble cara probablemente estaba dibujado antes que el anverso más conocido con sus meditados estudios con tiza roja; muchos de los dibujos de Miguel Ángel para las primeras partes del Techo Sixtino están realizados con una técnica similar de tiza negra suave (ejemplos de los primeros estudios de la Sixtina en tiza negra suave son el Museo Británico inv. 1859,0625.567, Londres; el Museo Teylers inv. A 18 verso, Haarlem; Casa Buonarroti inv. nos. 64 F y 75 F, Florencia; Musée du Louvre Département des Arts Graphiques inv. 860, París; Biblioteca Reale inv. 15627 DC, Turín.), mientras que una preponderancia de hojas realizadas para las partes posteriores de los frescos están pintados con tiza roja. El reverso de la hoja Metropolitan retrata en el centro, de perfil, la gran figura sentada y desnuda de la sibila (aquí, las formas anatómicas más suaves pueden ser femeninas, en lugar de masculinas como evidentemente lo son en el caso de los estudios del anverso), en arriba a la derecha un diseño muy resumido de una figura mucho más pequeña en vista de tres cuartos mirando hacia la izquierda (su estilo generalmente se parece a los motivos del "Oxford Sketchbook": ver Ashmolean Museum nos. 1846.45 a 1846.52), y en la parte inferior derecha el estudio detallado de la rodilla derecha de la sibila. El estudio principal a tiza roja, en lo que hoy se considera el anverso de la hoja de doble cara Metropolitan, retrata al joven sentado con la cabeza de perfil, los brazos doblados y la parte superior del cuerpo girada en una elegante postura de contrapposto, para mostrar la formidable musculatura de su atrás en una vista trasera. Miguel Ángel consideró con especial atención la posición de los hombros volviéndose hacia la profundidad del espacio, indicando también con dos pequeños círculos la prominencia de los músculos supraespinosos (los acentos con pequeños toques de tiza blanca en el hombro izquierdo son probablemente un retoque posterior, pero crear un punto culminante más intenso). La secuencia de ejecución de los motivos circundantes en el recto, también realizados con tiza roja, es mucho menos clara, y uno puede aventurarse a adivinar que, a la izquierda, la repetición de la cabeza de perfil y el boceto del torso y la cabeza fueron dibujados antes del estudio principal (dado que partes de sus contornos parecen estar debajo del estudio principal), mientras que los motivos altamente representados de la mano izquierda en la parte inferior central y las tres repeticiones del pie izquierdo y los dedos del pie derecho probablemente siguieron el estudio principal. estudiar en la hoja. La forma de soportar el peso de los dedos del pie izquierdo de la sibila fue crucial para el diseño general de la pose de contrapposto de la figura y explica los múltiples estudios de este detalle en la hoja Metropolitan. Los rasgos faciales de la gran cabeza en la parte inferior izquierda del anverso parecen más cercanos a los de la sibila libia del fresco final que al rostro del joven del estudio principal. El anverso de una hoja en el Museo Ashmolean (no. 1846.43; Fig. 2), Oxford, dedicada a estudios para el Techo Sixtino y bocetos para la Tumba del Papa Julio II, representa en el centro al joven genio asistente que es visto inmediatamente a la izquierda de la sibila libia pintada al fresco, así como en la parte inferior izquierda la mano derecha de la sibila, ambos motivos ejecutados con tiza roja. Si bien las dimensiones totales de la sábana Oxford (28,6 x 19,4 cm) son similares a las de la sábana Metropolitan, el tono de la tiza roja parece más brillante y ligeramente anaranjado; sin embargo, está claro que las hojas de Oxford y Nueva York son compañeras muy cercanas, probablemente del mismo cuaderno de bocetos, sin que sean necesariamente (en la opinión del presente autor) mitades de la misma hoja, como sugirió una generación anterior de estudiosos (resumen de discusión en Joannides 2007, p.120). Los hallazgos científicos que surgieron durante la limpieza de los frescos Sixtinos de Miguel Ángel (1984-1990; publicados en Mancinelli 1994) proporcionan un contexto preciso, aunque a menudo pasado por alto, en el que considerar la datación y la función de los estudios del Museo Metropolitano. Dado que el gran artista pintó la enorme bóveda de la capilla desde el extremo oeste hasta el este - es decir, desde arriba de la entrada hasta encima del sitio del altar - en dos campañas demarcadas por el montaje de andamios (o pontate), Como lo sugieren ambos documentos y una variedad de datos físicos surgidos recientemente (para los cuales ver Mancinelli 1994, pp. 16-22), la monumental Sibila libia pertenece a la última fase del trabajo en el proyecto. En este punto, el virtuosismo técnico de Miguel Ángel como pintor de frescos estaba en su apogeo, después de haber tenido un comienzo tosco e inexperto en 1508 cuando la primera escena de la bóveda que pintó al fresco, El Diluvio, creció moho debido a un intonaco preparado incorrectamente (este fino yeso de superficie se usó demasiado aguado; ver también Condivi 1553). La técnica de pintura más difícil es posiblemente la del fresco, ya que requiere rapidez de ejecución sobre el yeso húmedo antes de que fragüe y una gran confianza en uno mismo; los escritores de tratados de arte de los siglos XIV al XVIII juzgaron que el fresco era un medio supremo, precisamente por el virtuosismo técnico que exigía (Bambach 1999); como el propio Miguel Ángel se quejaría más tarde a su biógrafo Giorgio Vasari: "La pintura al fresco no es un arte para ancianos". (Vasari 1568). Aunque se debate la cronología del Techo Sixtino, la primera fase del trabajo, o pontata, se realizó entre finales del verano, tal vez finales de julio, de 1508 (el contrato para los frescos Sixtinos data del 10 de mayo de 1508). ; ver Bardeschi Ciulich y Barocchi 1970) y finales de agosto de 1510, y terminó con la pintura de la Creación de Eva; mientras que la segunda pontata y fase final del trabajo probablemente comenzó algún tiempo después de enero de 1511 (los meses de invierno no son buenos para pintar frescos), concluyendo el 31 de octubre de 1512 con la inauguración de la Capilla (ver Gilbert 1994). El recto del estudio del Museo Metropolitano puede fecharse con gran probabilidad en el invierno de 1511, cuando Miguel Ángel sabía dibujar en lugar de pintar al fresco (regresó a Roma, desde Bolonia, el 11 de enero de 1511), y habría sido preparado en al comienzo de la segunda pontata, es decir, poco después de que el gran artista hubiera movido su andamio por segunda (y última) vez para pintar. La gigantesca figura de la sibila libia, junto con su trono y sus asistentes, fue pintada al fresco en la gran superficie cóncava de la bóveda en veinte días de trabajo (el fresco se compone de 20 giornate, o parches de fina superficie de yeso), y el complejo el diseño se transfirió mediante la laboriosa técnica del spolvero (una caricatura o un dibujo a escala natural transferido mediante pinchazos y golpes en los contornos; véase Bambach 1994). El estudio Metropolitan está realizado con una tiza roja de tono ligeramente violáceo afilada en punta para los finos contornos de la figura y parte del sombreado interior, pero en ocasiones también se aplicaba con el costado del palo; el medio de tiza roja era especialmente adecuado para el estudio particularizado y altamente naturalista de los detalles anatómicos. Aunque Miguel Ángel había comenzado a utilizar tiza roja a principios de la década de 1490 (Ver CC Bambach, "La virtù dei disegni del giovane Michelangelo", en Michelangelo 1564-2014, ed. por C. Acidini, Roma 2014), sus mayores logros con este medio están conectados con las últimas partes del Techo Sixtino. Sin embargo, el grupo de estudios con tiza roja para la Sixtina también ha estado entre los dibujos de Miguel Ángel más controvertidos en términos de atribuciones. Los compañeros más cercanos en estilo y técnica a la Sibila libia metropolitana de tiza roja son los estudios sobre la hoja en el Museo Ashmolean (Fig. 2), así como otros tres en el Museo Teyler, Haarlem (núms. inv. A16 anverso, A20 recto-verso y A27 recto-verso). De hecho, dos de estas hojas de Teyler (A20 y A 27) están dibujadas con una tiza roja de tono violáceo muy similar a la empleada para la Sibila libia en el anverso de la hoja del Museo Metropolitano. Claramente autógrafos, los bocetos en el reverso mejor conservado de la hoja Metropolitan nunca son mencionados por los estudiosos que rechazan la atribución de los estudios del recto a Miguel Ángel (Perrig 1976; Perrig 1991; Zöllner et al. 2008). Este reverso exhibe un tipo de manejo similar, con sombreados y contornos sueltos e impresionistas, en lugar de detalles finos, como la mayoría de los estudios con tiza negra suave para las primeras partes del Techo Sixtino (por ejemplo, las láminas inv del Museo Británico). . 1859,0625.567, Londres; Teylers Museum inv. A 18 verso, Haarlem; Casa Buonarroti inv. nos. 64 F y 75F, Florencia; Musée du Louvre Département des Arts Graphiques inv. 860, París). La copia de finales del siglo XVI en tiza roja según la Sibila libia metropolitana de los Uffizi (n.º inv. 2318 F), Florencia, es casi del mismo tamaño, pero tiene una calidad de ejecución notablemente inferior, omitiendo también las dos notaciones anatómicas. de círculos en los hombros y los pequeños detalles en tiza blanca. Además, la copia dibujada reordena la posición de los motivos individuales, introduce el pie derecho de la sibila (que está ausente en el anverso de la hoja Metropolitana) y registra el final abrupto de los contornos en el estudio del dedo del pie. Como la copia de los Uffizi emula defectos de estado de la hoja Metropolitan original (especialmente los contornos del agujero en el soporte de papel original), se puede deducir que deriva directamente de la hoja Metropolitan. Los bocetos al reverso de la hoja del Museo Metropolitano siempre han sido reconocidos, con razón, como obra de Miguel Ángel, y el "núm. 2i". La inscripción en la parte inferior central añade una prueba más, ya que encaja precisamente en una secuencia numérica que se encuentra en muchos otros dibujos del gran artista que tienen una procedencia temprana de la familia Buonarroti (ver Bambach 1997). La anotación en la parte inferior izquierda del anverso sobre el apellido del artista, escrito aquí con la forma "bona Roti", también es significativa a la vista del corpus de dibujos de Miguel Ángel y su escuela que llevan esta anotación del llamado "Bona Roti". coleccionista", como le ha bautizado Paul Joannides. En cualquier caso, importantes grupos de dibujos heredados por la familia Buonarroti parecen haber estado dispersos entre ca. 1684 y 1799, probablemente por el senador Filippo Buonarroti (Joannides 2007). El párrafo escrito con pluma y tinta marrón oscuro inscrito en la parte inferior central del anverso de la hoja Metropolitan se confunde a menudo con una marca de propiedad del coleccionista Everhard Jabach (1618-1695), de Colonia y París (De Tolnay 1975; Logan y Plomp 2005). ) más bien se parece mucho a los paráfos garabateados en hojas de dibujos de la Real Academia de San Fernando de Madrid, y que formaban parte de un nutrido grupo de dibujos adquiridos en 1775 a la viuda del pintor Andrea Procaccini (1671-1734), que había fallecido en La Granja de San Ildefonso y que a su vez los había heredado de su maestro, Carlo Maratti (1625-1713; véase Mena Marqués 1982). Aunque el estado general de esta hoja de doble cara es muy bueno, es algo diferente para cada cara del papel; el tono blanquecino original del papel todavía está casi intacto en el reverso, pero está considerablemente oscurecido en el anverso; aparentemente esto se debe a la exposición prolongada a la luz y, como señaló en 1925 Bryson Burroughs (el curador que compró el dibujo para el Met), los estudios con tiza roja en el anverso fueron "fijados" con una solución de goma laca en alcohol. lo que ha intensificado las diferencias de luz y sombra (Bryson Burroughs 1925). El recto también presenta manchas de lavado marrón en la parte inferior derecha; la pérdida triangular en el soporte original hacia el centro del borde derecho (si se mira la hoja desde el anverso) es el resultado de un daño muy temprano, siendo reparado y tonificado en una restauración posterior a 1951. (Carmen C. Bambach)

Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto); Studies for the Libyan Sibyl and a small Sketch for a Seated Figure (verso). Artist: Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, Caprese 1475-1564 Rome). Dimensions: Sheet: 11 3/8 x 8 7/16 in. (28.9 x 21.4 cm). Date: ca. 1510-11.

This double-sided sheet of closely observed life studies is the most magnificent drawing by Michelangelo in North-America, purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art on August 8, 1924 (its acquisition being voted by the museum's acquisitions committee on June 9, 1924), in great part thanks to negotiations by the eminent painter, John Singer Sargent, with the widow of Aureliano de Beruete, its previous owner (file no. D7950, Archive Department of Drawings and Prints, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). The much smaller than life-size studies on the famous recto side of the Metropolitan sheet were clearly done from a young male assistant posing in the artist's studio, being preparatory for the design of the Libyan Sibyl, the monumental enthroned female figure painted in fresco on the north-east end of the Sistine Ceiling. The Libyan Sibyl was the last of the seers to be frescoed on the north part of the vault, executed in a scale that is about three times life-size (the overall area of this part in the fresco measures 4.54 meters by 3.80 meters); she is clothed except for her powerful shoulders and arms, and wears an elaborately braided coiffure. Her complex pose in the fresco, evidently requiring study in numerous drawings, plays on the arrested motion of her stepping down from the throne, while holding an enormous open book of prophecy which she is about to close.

Sketched in soft black chalk, the verso of the double-sided Metropolitan sheet was possibly drawn before the better-known recto side with its meditated red chalk studies; many of Michelangelo's drawings for the early parts of the Sistine Ceiling are in a similarly soft black-chalk technique (examples of early Sistine studies in soft black chalk are British Museum inv. 1859,0625.567, London; Teylers Museum inv. A 18 verso, Haarlem; Casa Buonarroti inv. nos. 64 F and 75 F, Florence; Musée du Louvre Département des Arts Graphiques inv. 860, Paris; Biblioteca Reale inv. 15627 D.C., Turin.), while a preponderance of sheets done for the later parts of the frescoes are in red chalk. The verso of the Metropolitan sheet portrays at center, in profile the large nude seated figure of the sibyl (here, the softer anatomical forms may be feminine, rather than masculine as they evidently are in the case of the studies on the recto), at upper right a very summary design of a much smaller figure in three-quarter view facing left (its style generally resembles the motifs in the "Oxford Sketchbook": see Ashmolean Museum nos. 1846.45 to 1846.52), and at lower right the detail study of the sibyl's right knee. The main study in red chalk, on what is today considered the recto of the Metropolitan double-sided sheet, portrays the seated youth with head in profile, bent arms and upper body turned in an elegant contrapposto stance, to display the formidable musculature of his back in a rear view. Michelangelo considered the position of the shoulders turning into the depth of space, with especial attention, indicating also with two small circles the prominence of the supraspinatus muscles (the accents with tiny touches of white chalk on the left shoulder are likely a later retouching, but create a most intense highlight).

The sequence of execution of the surrounding motifs on the recto, also done in red chalk, is much less clear, and one may venture to guess that, at left, the reprise of the head in profile and the rough sketch of the torso and head were drawn before the main study (given that parts of their outlines seem to lie underneath the main study), while the highly rendered motifs of the left hand at lower center and the three reprises of the left foot and toes at right probably followed the main study on the sheet. The manner of the weight-bearing on the toes of the sibyl's left foot was crucial for the overall design of the figure's contrapposto pose, and explains the multiple studies of this detail on the Metropolitan sheet. The facial features on the large head at lower left in the recto seem closer to those of the Libyan Sibyl in the final fresco, than the face of the youth in the main study. The recto of a sheet in the Ashmolean Museum (no. 1846.43; Fig. 2), Oxford, dedicated to studies for the Sistine Ceiling and sketches for the Tomb of Pope Julius II, represents at center the attendant young boy genius who is seen to the immediate left of the frescoed Libyan Sibyl, as well as at lower left the sibyl's right hand, both motifs executed in red chalk. While the overall dimensions of the Oxford sheet (28.6 x 19.4 cm) are similar to those of the Metropolitan sheet, the hue of the red chalk seems brighter and slightly orange; nevertheless, it is clear that the Oxford and New York sheets are very close companions, probably from the same sketchbook, without their necessarily being (in the present author's opinion) halves of the same sheet, as an earlier generation of scholars suggested (summary of discussion in Joannides 2007, p. 120).

The scientific findings which emerged during the cleaning of Michelangelo's Sistine frescoes (1984-1990; published in Mancinelli 1994) provide a precise, though often overlooked context in which to consider the dating and function of the Metropolitan Museum studies. Given that the great artist painted the enormous vault of the chapel from the west to east end -- that is, from above the entrance to above the site of the altar -- in two campaigns demarcated by the erection of scaffolding (or pontate), as is suggested by both documents and a variety of recently emerged physical data (for which see Mancinelli 1994, pp. 16-22), the monumental Libyan Sibyl belongs to the latter phase of work on the project. At this point, Michelangelo's technical virtuosity as a fresco painter was at its height, having made a rough and inexperienced beginning in 1508 when the first scene of the vault he frescoed, The Deluge, grew mold because of incorrectly prepared intonaco (this fine surface plaster was used too watery; see also Condivi 1553). The most difficult technique of painting is possibly that of fresco, as it requires speed of execution onto the wet plaster before it sets and great self-confidence; writers of art treatises from the fourteenth to the eighteenth century judged the medium of fresco to be supreme, precisely because of the technical virtuosity it demanded (Bambach 1999); as Michelangelo would himself later complain to his biographer Giorgio Vasari: "Fresco painting is not an art for old men." (Vasari 1568).Although the chronology of the Sistine Ceiling is debated, the first phase of work, or pontata, was done between late summer - perhaps late July -- of 1508 (the contract for the Sistine frescoes dates to May 10, 1508; see Bardeschi Ciulich and Barocchi 1970) and late August 1510, and ended with the painting of the Creation of Eve; while the second pontata and final phase of work probably began some time after January 1511 (the winter months are not good for fresco-painting), concluding on October 31, 1512 with the unveiling of the Chapel (see Gilbert 1994). The recto of the Metropolitan Museum study can be dated with great probability to the winter of 1511, when Michelangelo could draw rather than paint in fresco (he returned to Rome, from Bologna, by January 11, 1511), and would have been prepared at the beginning of the second pontata, that is, soon after the great artist had moved his scaffolding for the second (and final) time to paint. The gigantic figure of the Libyan Sibyl, together with her throne and attendants, was frescoed onto the large concave surface of the vault in twenty days of work (the fresco is comprised of 20 giornate, or patches of fine surface plaster), and the complex design was transferred by the laborious technique of spolvero (a cartoon or full-scale drawing transferred by means of pricking and pouncing the outlines; see Bambach 1994).

The Metropolitan study is done with a red-chalk of slightly purplish hue sharpened to a point for the fine contours of the figure and some of the interior hatching, but it was also at times applied with the side of the stick; the red chalk medium was especially suited for the particularized, highly naturalistic study of anatomical detail. Although Michelangelo had begun to use red chalk in the early 1490s (See C.C. Bambach, "La virtù dei disegni del giovane Michelangelo", in Michelangelo 1564-2014, ed. by C. Acidini, Rome 2014), his greatest accomplishments with this medium are connected with the later parts of the Sistine Ceiling. Yet the group of red chalk studies for the Sistine has also been among the most greatly contested of Michelangelo's drawings in terms of attributions. The closest companions in style and technique to the red-chalk Metropolitan Libyan Sibyl are the studies on the sheet at the Ashmolean Museum (Fig. 2), as well as three others at the Teyler Museum, Haarlem (inv. nos. A16 recto, A20 recto-verso, and A27 recto-verso). Two of these Teyler sheets (A20 and A 27) are drawn, in fact, with a red chalk of closely similar purplish hue as that employed for the Libyan Sibyl on the recto of the Metropolitan Museum sheet. Clearly autograph, the sketches on the better preserved verso of the Metropolitan sheet are not ever mentioned by the scholars rejecting the attribution of the recto studies to Michelangelo(Perrig 1976; Perrig 1991; Zöllner et al. 2008). This verso exhibits a similar type of handling --with loose, impressionistic hatching and contours, rather than finely detailed-- as most of the soft black-chalk studies for the early parts of the Sistine Ceiling (for example, the sheets British Museum inv. 1859,0625.567, London; Teylers Museum inv. A 18 verso, Haarlem; Casa Buonarroti inv. nos. 64 F and 75F, Florence; Musée du Louvre Département des Arts Graphiques inv. 860, Paris). The late sixteenth-century copy in red chalk after the Metropolitan Libyan Sibyl at the Uffizi (inv. no. 2318 F), Florence, is of nearly the same size, but is of remarkably inferior quality of execution, omitting also the two anatomical notations of circles on the shoulders and the tiny white chalk accents. Moreover, the drawn copy rearranges the positioning of the individual motifs, introduces the right foot of the sibyl (which is absent in the recto of the Metropolitan sheet), and records the abrupt terminus of outlines in the study of the toe. As the Uffizi copy emulates defects of condition in the original Metropolitan sheet (especially the outlines of the hole in the original paper support), it can be deduced that it directly derives from the Metropolitan sheet.

The verso sketches on the Metropolitan Museum sheet have always rightly been recognized as by Michelangelo, and the "no. 2i ." inscribed at lower center adds further proof, as it fits precisely into a numerical sequence found on many other drawings by the great artist that have an early Buonarroti family provenance (see Bambach 1997). The annotation at lower left on the recto regarding the artist's surname, here spelled in the form of "bona Roti" is also signficant in view of the corpus of drawings by Michelangelo and his school which bear this annotation by the so-called "Bona Roti collector," as Paul Joannides has baptized him. In any case, important groups of drawings inherited by the Buonarroti family appears to have been dispersed between ca. 1684 and 1799, probably by the senatore Filippo Buonarroti (Joannides 2007). The paraph in pen and dark brown ink inscribed at lower center on the recto of the Metropolitan sheet is often mistaken as a mark of ownership by the collector Everhard Jabach (1618-1695), of Cologne and Paris (De Tolnay1975; Logan and Plomp 2005) rather, it closely resembles the paraphs scribbled on sheets of drawings in the Real Academia de San Fernando, Madrid, and which were part of a large group of drawings acquired in 1775 from the widow of the painter Andrea Procaccini (1671-1734), who had died at La Granja de San Ildefonso and who had in turn inherited them from his master, Carlo Maratti (1625-1713; see Mena Marqués 1982). Although the overall condition of this double-sided sheet is very good, it is somewhat different for each face of the paper; the original off-white hue of the paper is still nearly intact on the verso, but is considerably darkened on the recto; this is apparently due to prolonged exposure to light, and, as noted in 1925 by Bryson Burroughs (the curator who bought the drawing for the Met), the red chalk studies on the recto were "fixed" with a solution of shellac in alcohol, which has intensified the differences of light and shade (Bryson Burroughs 1925). The recto also exhibits stains of brown wash at lower right; the triangular loss on the original support toward the center of the right border (if the sheet is regarded from the recto) is the result of very early damage, being made up and toned in restoration after 1951.

(Carmen C. Bambach).

Técnica/material:

Red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study (recto); soft black chalk, or less probably charcoal (verso)

Museo:

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Crédito:

Album / Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Autorizaciones:

Modelo: No - Propiedad: No

¿Preguntas relacionadas con los derechos?

¿Preguntas relacionadas con los derechos?

Tamaño imagen:

2927 x 3970 px | 33.2 MB

Tamaño impresión:

24.8 x 33.6 cm | 9.8 x 13.2 in (300 dpi)

Palabras clave:

Pinterest

Pinterest Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Copiar enlace

Copiar enlace Email

Email